/*

"WE The People: Mr. Johnson and Mr. Lincoln in America"

The Opinion Pages - Opinionator:

http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/02/01/mr-lincoln-and-mr-johnson/?_r=0

Opinionator - A Gathering of Opinion From Around the Web

Disunion

Mr. Lincoln and Mr. Johnson

By

Phillip W. Magness and Sebastian Page

The New York Tiimes, February 1, 2012 9:30 pm February 1, 2012

Disunion

Disunion follows the Civil War as it unfolded.

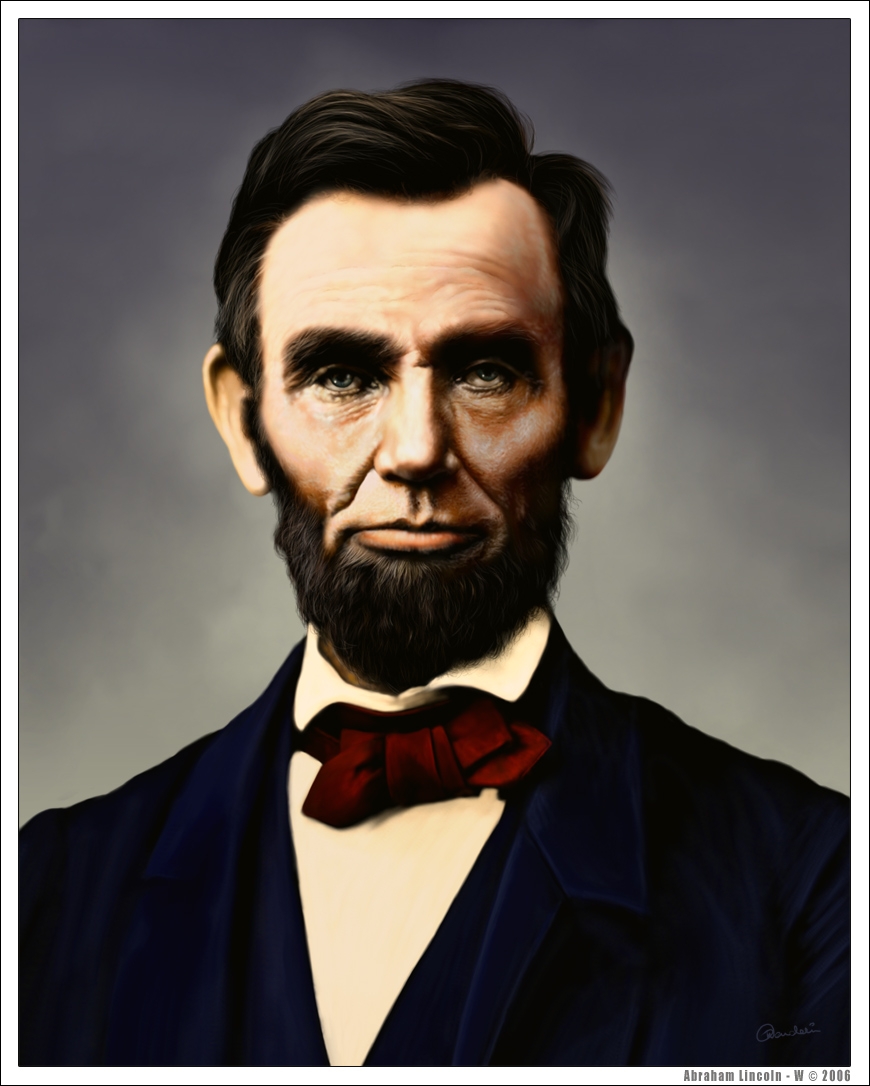

One day in early 1864, a journalist found Abraham Lincoln busy counting greenbacks. “This, sir, is something out of my usual line,” the president told the reporter, “but a president of the United States has a multiplicity of duties not specified in the Constitution or acts of Congress.” The money belonged to a porter in the Treasury Department who was in the hospital and so ill from smallpox that he could not even draw his pay. The president had collected the outstanding wages himself and was dividing them into envelopes in accordance with the porter’s wishes.

What makes Lincoln’s concern for a low-ranking employee all the more remarkable is that the man was also an African-American.

Today we know little about that man, William H. Johnson. He has no surviving photograph, and we can only speculate as to his age, although there are strong hints that he was at least in his mid-20s. He was, however, very close to the president: the earliest records of him show that he began doing menial jobs for the Lincoln family in Springfield, Ill., around 1860 and soon accompanied them to Washington.

The working relationship between the two men attests to the complex and even enigmatic nature of Lincoln’s racial attitudes. Indeed, the mystery that surrounds Johnson’s death, and Lincoln’s sense of responsibility for it, tells us much about the “Great Emancipator’s” complex relationship with African Americans and their quest for full citizenship.

Shortly after his arrival in the capital, the president referred to the adult Johnson as a “colored boy,” attaching a belittling racial convention to the man he described as his “servant.” At the same time, a more glaring display of racism quickly brought Lincoln to his valet’s defense. Within a week of his arrival, Johnson fell victim to the rigid hierarchies of the White House staff, where lighter-skinned servants traditionally received preferential rank and responsibilities.

Aware that prejudice had overshadowed Johnson’s ability, the president secured him a messenger’s post at the Treasury Department. “The difference of color between him and the other servants is the cause of our separation,” explained Lincoln. “I have confidence as to his integrity and faithfulness.”

And while he shared a racial view typical of many white northern moderates, Lincoln clearly thought highly of Johnson.

Even after Johnson left for the Treasury, Lincoln allowed him to do side work as his barber and valet to eke out a living, wrote him checks to tide him over and apparently trusted him with carrying large sums of money. The president occasionally requested to borrow Johnson’s services from the Treasury for a whole day or two, and Johnson accompanied Lincoln on his famous trip to Gettysburg on Nov. 18, 1863.

Even as Lincoln delivered his address, he was coming down with disease. Most accounts say that Lincoln had varioloid, the milder form of smallpox, but recent research suggests that he actually had a more serious strain and that his life was in very real danger. Whatever the case, the president recovered; his valet, who tended to Lincoln in those early stages, was not so lucky. Johnson contracted smallpox and died sometime between Jan. 11 and Jan. 28, 1864.

Washington was in the grip of a smallpox epidemic, so it was impossible to chart its transmission from person to person.

“He did not catch it from me,” explained Lincoln. “At least I think not.” Whether through a nagging sense that he was responsible, or on the strength of their warm relationship – likely both – the president helped close his deceased servant’s affairs. “William is gone,” rued Lincoln to a Washington banker. “I bought a coffin for the poor fellow, and have had to help his family.”

A Treasury clerk later confirmed that the “president had him buried at his expense.” The anecdote reveals Lincoln’s humanity at its best and appeared in a Republican campaign biography later that year, albeit stripped of any hint that Johnson may have contracted the disease from the president.

Such is the tale’s magnetic appeal that it has subsequently picked up three embellishments. First, that Johnson’s grave is still visible today at Arlington cemetery. Second, that Lincoln personally paid for his headstone. And third, that he personally ordered the stone inscribed “citizen,” thereby symbolically repudiating the Supreme Court’s notorious Dred Scott decision. All three, together, offer an attractive but misleading insight on Lincoln’s views about African-American citizenship.

The story of Johnson’s death is not much clearer than that of his life, since the chaos of war left death and burial records in disarray. Roy Basler, editor of Lincoln’s “Collected Works,” wondered if his grave was at Arlington on a “hunch,” and duly found one William H. Johnson in Plot 3346, Section 27, whose corresponding burial record for an avowedly imprecise “1864” seemed to fit the bill. And the tombstone does indeed read “Citizen.” Still, Johnson’s name was a common one and the Custis-Lee estate’s official conversion to a cemetery was still several months away when Johnson died (though there are hints of earlier, unrecorded burials thereabouts). Is it him, and if so, why would Lincoln have him buried there?

Another Lincoln biographer has accordingly placed Johnson in the Congressional Cemetery, while a local Washington historian, Tim Dennee, states that most black smallpox victims found their way to the Columbian Harmony Cemetery, in the capital’s Northeast quadrant. Unfortunately, that site was cleared half a century ago for development.

What, then, are we to make of the supposed gravestone, or the accompanying tale of Lincoln’s posthumous grant of citizenship to Johnson? Like others in the vicinity, the stone of the elusive “William H. Johnson” at Arlington is a 1990s replacement, though it repeats the original epitaph, “citizen.” Yet this part of the cemetery is crowded with “citizens.”

Rather than conferring citizenship on the interred, the authorities merely wanted to make it clear that civilians, rather than soldiers, had been buried there during Arlington’s earliest days, before it was restricted to the military. While it is not inconceivable that Lincoln tried to guarantee Johnson a marker of some description at an unknown location, he certainly had nothing to do with the stone we see today at Arlington, or its predecessor, which replaced a wooden headboard no sooner than 1877, or either’s inscription of “citizen.”

Related

Disunion Highlights

Fort Sumter:

Explore multimedia from the series and navigate through past posts, as well as photos and articles from the Times archive.

Ultimately, it’s unclear what the term “citizen” even meant to the president. While Lincoln trod a fine line between his personal contempt for the Dred Scott decision, which denied citizenship to African-Americans, and public respect for the law, his attorney general, Edward Bates, lambasted the decision’s distinction between national and state citizenship in a legal opinion of November 1862. Still, Bates could find no single definition of “citizen,” and observed that it sometimes meant “civilian,” in opposition to “soldier”; he also stressed that his opinion was only meant for free African Americans, not slaves, and that individual citizenship meant nothing with regards to the right to vote.

Bates’s opinion was likely in keeping with the president’s views, though Lincoln offered no comment and did not personally address the issue of African-American citizenship between some brief remarks in 1858 and his death. Perhaps more significantly, Lincoln did tentatively recommend the vote for black veterans and “very intelligent” African Americans by the end of his life.

Abraham Lincoln enjoyed a warm relationship with his valet, but also wrote of him and his replacement as “boy.” We need hardly single out the president for such common usage to appreciate that it sits uneasily with placing so much weight on another solitary word, “citizen.” That was not Lincoln’s choice of inscription, and although the very suggestion of Black citizenship could repel and inspire his contemporaries in equal measure, it is doubtful that an antislavery moderate would have deployed it as some kind of symbolic affirmation or withheld it as a calculated snub. It was a predominantly technical term, albeit one that ironically lacked definition. Its meaning to Lincoln died with him in 1865.

Follow Disunion at twitter.com/NYTcivilwar or join us on Facebook.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Sources: Roy P. Basler, “The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln,” “Did President Lincoln Give the Smallpox to William H. Johnson?” and “President Lincoln Helps His Old Friends”; Edward Bates, “Opinion on Citizenship”; Mark Benjamin, “Vanishing History at Arlington Cemetery”; Gabor Boritt, “The Gettysburg Gospel”; Michael Burlingame, “Abraham Lincoln: A Life”; James Cornelius, “William H. Johnson, Citizen”; Tim Dennee, “African-American Civilians Interred in Section 27 of Arlington National Cemetery”; Eric Foner, “The Fiery Trial”; James Oakes, “Natural Rights, Citizenship Rights, States’ Rights, and Black Rights”; Robert M. Poole, “On Hallowed Ground”; John E. Washington, “They Knew Lincoln.”

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Phillip Magness and Sebastian Page

Phillip W. Magness, the academic program director at the Institute for Humane Studies, at George Mason University, and Sebastian Page, a junior research fellow at the Queen’s College and Rothermere American Institute at Oxford, are the co-authors of “Colonization After Emancipation: Lincoln and the Movement for Black Resettlement.” The authors would like to thank Patrick Andelic, James Cornelius and Tim Dennee for their help.

~Courtesy of Philip W. Magness~

and

Re-Posted by

Gregory V. Boulware, ASB/CS-CP

http://www.BoulwareEnterprises.com

William H. Johnson

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_H._Johnson

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

and

http://www.PBS.com

WHYYTV12 in Philadelphia

William Henry Johnson, (c. 1835 – January 28, 1864) was a free African American, and the personal valet of Abraham Lincoln. Having first met Lincoln in Springfield, Illinois, he accompanied the President-Elect to Washington, D.C.[1] Once there, he was employed in various jobs, part-time as President's valet and barber, and as a messenger for the Treasury Department at $600 per year.

Biography:

William Henry Johnson was born around 1835 at a site unknown. He began working for Abraham Lincoln, in Springfield, in early 1860.

Smallpox:

On November 18, 1863, Johnson traveled by train with Lincoln to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania for the dedication of the Soldiers' National Cemetery, where Lincoln delivered the Gettysburg Address. On the return trip, Lincoln became ill with what turned out to be smallpox.

Johnson tended to him, and by January 12, 1864 was himself sick with the disease. Lincoln recovered, but by January 28, Johnson was dead.

Burial:

Lincoln arranged for and paid for Johnson's burial in January 1864 and paid for his headstone. Burial records from the time were not well kept and at least three competing locations have been proposed for Johnson's grave. The most popular is a William H. Johnson who was buried in 1864 at Arlington National Cemetery, although his common surname makes a conclusive match impossible. Contrary to a popular myth though, Lincoln did not purchase the headstone that appears there now.

Arlington ordered a new stone and inscribed on it Citizen, which was the label used to distinguish civilian graves from soldiers before Arlington became an exclusively military cemetery.[3]

In popular culture:

William H. Johnson was a character in the 2012 film Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter, played by actor Anthony Mackie. In the movie, Lincoln and Johnson are portrayed as childhood friends. In the film's opening scene, a young Lincoln rushes to the aid of a young Johnson, who is being whipped by a slaver. Johnson then goes on to work in the Lincoln White House and assist President Lincoln in his fight against the vampiric forces of the Confederate Army.

*/

http://www.bing.com/search?q=Lincoln+and+Mr.+Johnson%2C+his+butler&form=PRUSEN&mkt=en-

http://www.bing.com/search?q=Lincoln+and+Mr.+Johnson%2C+his+butler&form=PRUSEN&mkt=en-us&refig=39278947901b456d8fca751000b8b10b&pq=lincoln+and+mr.+johnson%2C+his+butler&sc=0-23&sp=-1&qs=n&sk=&cvid=39278947901b456d8fca751000b8b10b

Posted By: Gregory V. Boulware, Esq.

Posted By: Gregory V. Boulware, Esq.

Monday, September 21st 2015 at 6:57PM

You can also

click

here to view all posts by this author...